(LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/from-telegraph-terawatt-hours-why-nato-l-could-great-eastern-marcoux-thhme/)

In 1866, the Great Eastern steamship laid the first successful transatlantic telegraph cable, forever altering global communication. Messages that once took ten days to cross the Atlantic by ship could suddenly be sent in minutes. The geopolitical, commercial, and cultural impacts were immediate and profound — not because the cable was cheap, but because it was transformative.

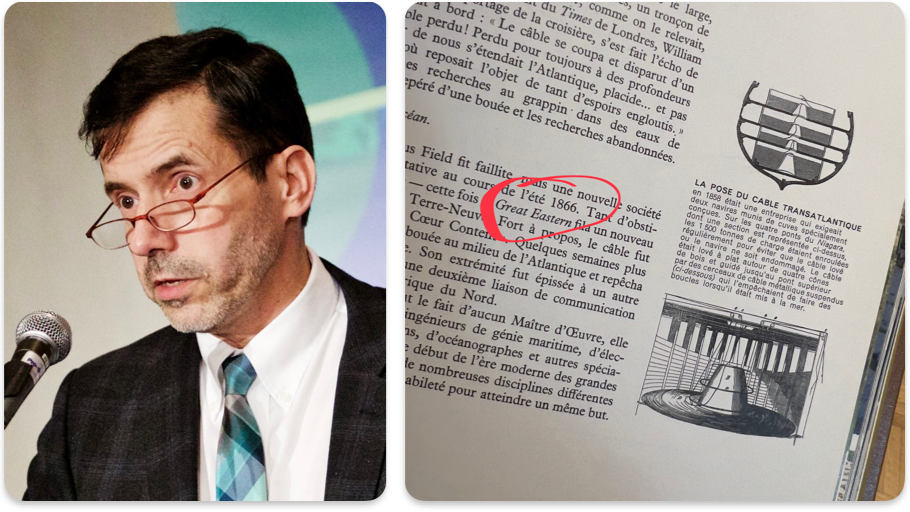

I remember reading about the Great Eastern when I was young, and its audacious scale and engineering left a lasting impression on me. (The picture accompanying this article is from one of my books when I was a kid.) It was a tool of its time — a giant that bridged continents — and it sparked my lifelong interest in the power of big systems to shape the world.

Today, a similar revolution may be taking shape below the waves. Proposed by three energy financiers, Laurent Segalen , Simon Ludlam , and Gerard Reid , the North Atlantic Transmission One – Link (NATO-L) project aims to connect Canada’s hydroelectric and renewable energy sources with Europe’s renewable grid. It would create a high-capacity, high-voltage direct current (HVDC) lines between North America and Europe.

But I don’t think that this is just about moving electrons. Like the first transatlantic telegraph cable, NATO-L could reshape geopolitical relationships, catalyze economic integration, and unlock a new era of clean energy cooperation — if we get the market structures right for power producers at both ends to benefit.

Before proceeding, I must clarify that I have no financial, professional, or personal interest in the NATO-L project. Additionally, I was neither compensated nor requested by its proponents to write this article. My analysis is based solely on publicly available information and my independent interpretation of its implications.

A Project of Strategic Proportions

The NATO-L cable would link two complementary energy systems:

- North-eastern North America, with abundant and dispatchable hydroelectricity, as well as growing onshore and offshore wind capacity.

- Northern Europe, with enormous offshore wind generation and growing challenges around intermittency and curtailment.

Based on public information, NATO-L will consist of HVDC subsea cables (6 GW total capacity) using>525 kV technology, with routes ranging between 3,750 km and 4,500 km. I anticipate the project will be implemented in phases, each adding a few gigawatts of capacity over several years. This phased approach would allow for incremental learning and risk management, enabling stakeholders to better assess the project’s performance and value before committing to the full build-out.

Several routing options are also under evaluation, including northern (possibly via Greenland) and southern (via France) corridors. The shorter northern route, which I believe to be the most promising one, establishes a connection between hydroelectric power generation in northern Québec and Labrador and renewable energy sources in the North Sea and neighbouring countries.

The project leverages uncorrelated wind and solar resources across continents and a six-hour time difference to optimize renewable use and daily grid balancing. Operational commissioning is targeted for 2040 following a multi-phase development and permitting schedule.

Not About Cheap Power — About Timely Power

While legacy hydro in Eastern Canada is inexpensive, new capacity additions — whether hydro, wind, or solar — are increasingly costly. Meanwhile, wind and solar prices in Europe are declining. This means NATO-L’s value does not rest on permanent price gaps but on timing.

Thanks to the 5–6 hour time difference between Eastern North America and Europe, NATO-L enables daily arbitrage:

- Transmit power eastward during the peak demand periods of the morning and evening in Europe, which correspond to the low demand periods of midday and the middle of the night in Canada.

- Transmit power westward during the peak demand periods of the morning and evening in Canada, which correspond to the low demand periods of midday and the middle of the night in Europe.

This allows the same installed capacity to serve four peak demand periods per day, greatly enhancing system value.

Hydro as a Remote Battery for Europe

Unlike wind and solar, big hydro (with reservoirs) is dispatchable. The water stored in reservoirs can be released precisely when needed, although minimum flow and cascaded generating stations somewhat limit this flexibility. This allows North American hydro to serve as a zero-carbon remote battery for Europe:

- Curtailment mitigation: Back off hydro generation when European wind is abundant.

- Rapid dispatch: Ramp up hydro when Europe faces supply shortfalls.

- Balancing services: Support frequency regulation and grid stability, on and off peaks.

This turns Canadian hydro into powerful tools for enabling high penetration of renewables in Europe — by allowing water to be conserved in North American reservoirs when wind and solar are abundant in Europe, and dispatched when European generation is insufficient. This flexibility is especially valuable because days of high electricity demand are typically not correlated between Europe and Eastern Canada. This lack of correlation further strengthens the arbitrage and balancing potential of transatlantic interconnection. As coal and gas are phased out in Europe, this capability becomes increasingly critical, especially with the large inflexible French nuclear fleet in the mix.

European Experience with HVDC Submarine Interconnectors

Europe has extensive and growing experience with HVDC submarine interconnectors, including:

- Viking Link (UK—Denmark): 765 km, 1.4 GW, operational since 2023.

- North Sea Link (UK—Norway): 720 km, 1.4 GW, operational since 2021.

- NordLink (Germany—Norway): 623 km, 1.4 GW, operational since 2021.

- IFA2 (UK—France): 204 km, 1 GW, operational since 2021.

- COBRAcable (Netherlands—Denmark): 325 km, 700 MW, operational since 2019.

These interconnectors have proven to be highly effective at smoothing intermittent generation, lowering wholesale prices, and enhancing reliability during peak demand or system stress. While some of these projects were initially controversial due to concerns over cost, environmental impact, or market interference, their eventual success has demonstrated the technical and regulatory feasibility of long-distance HVDC links across sovereign borders — a precedent highly relevant to NATO-L.

Financial Framework: Costs and Value Potential

Submarine interconnectors are already widely used and deliver measurable value in regional grids. For example, during the 2024–25 winter in Great Britain, National Grid reported that its interconnector fleet provided up to 5.2 GW of dynamic flow changes in response to system stress, including the cancellation of emergency capacity notices. The Viking Link, initially operating at half capacity due to Danish grid maintenance, was promptly ramped up to full capacity to serve the British evening peak — a clear demonstration of the value of cross-border, real-time coordination. NATO-L would extend these proven benefits to a transatlantic scale, enabling load balancing between asynchronous grids and optimizing the use of uncorrelated renewable resources.

Financial Overview Table (estimation by me, not NATO-L):

Capital cost estimates for NATO-L are based on comparisons with similar long-distance HVDC subsea cable projects. For example, Viking Link (UK—Denmark, 1,400 MW over 765 km) cost around €2 billion, while the proposed Xlinks Morocco—UK project (3.6 GW, 4,000 km) is projected at £20 billion. NATO-L, at 6 GW and 3,750–4,500 km, is expected to cost between €20–28 billion, accounting for cable manufacturing, installation, converter stations, permitting, and contingencies. This figure also aligns with the cost profiles of other multi-gigawatt subsea projects using>525 kV HVDC technology.

Operating costs for a project of this scale include cable and station maintenance, staffing, insurance, regulatory compliance, and system operation. These costs are expected to range from €200 million to €500 million annually, depending on utilization and actual deployment complexity. The largest component is likely to be the energy cost associated with transmission losses, followed by routine subsea inspection and maintenance cycles, and the costs of keeping converter stations and control systems operating reliably across the oceanic span.

Transmission losses are an important factor in operating costs. HVDC subsea cables typically experience losses of about 3% per 1,000 km. Over the projected northern route of 3,750 km, this implies total line losses of roughly 11–12%. Losses would be less when the cables are not operating at full capacity. Assuming a 60% utilization rate (4 peaks of 3–4 hours each), a 6 GW line would deliver about 31.5 TWh/year. At a 12% loss, approximately 4 TWh/year is lost. Valued at €80/MWh, this represents an annual cost of roughly €320 million, falling within the upper range of operating expenditure estimates. This reinforces the importance of optimizing utilization and transmission efficiency for financial viability.

The projected €2–4.5 billion in annual available market value represents the pool of value created by energy arbitrage, capacity services, and ancillary grid functions. This is not necessarily revenue for NATO-L itself, as this value will be shared among all market actors involved — including electricity producers, storage operators, balancing service providers, and potentially the interconnector operator. NATO-L yearly revenue would depend on its regulatory framework, ownership structure, and the tolling or merchant model adopted.

1. Energy Arbitrage:

With a 6 GW line used 50–75% of the time, annual traded volumes would be 26–39 TWh.

Price spreads of €50–100/MWh between North American and European peak times yield a value pool of €1.3B to €3.0B per year.

2. Capacity Payments:

Capacity prices in European markets like the UK range from €30,000—€75,000/MW/year.

For 6 GW, this translates into €180M to €450M per year.

3. Ancillary Services and Curtailment Mitigation:

By avoiding curtailment and providing balancing support, NATO-L could enable services valued at €100M to €300M per year.

Total Justified Value Range: €1.6B (low end) to €4.5B+ per year (upper-bound).

This structure does not rely on permanent average price advantages, but on market-driven value creation through flexibility, timing, and integration services.

The proponents of NATO-L will likely rely on analytical approaches beyond traditional net present value (NPV) analysis to assess the viability of the project — as is often the case with transformative infrastructure initiatives. When faced with high uncertainty, long time horizons, and the potential for systemic impacts, methods such as real option analysis, scenario-based planning, and strategic value assessments are frequently more appropriate. This perspective reflects how other major interconnector projects have been evaluated and aligns with the inherently strategic nature of NATO-L.

The NATO-L project is clearly still in its early stages, focusing on building consensus, attracting founding members, and engaging with stakeholders across political, regulatory, technical, industrial, and financial sectors. Given the project’s scale and strategic importance, it is possible that major European utilities or transmission operators may become involved as the project progresses.

Modern Cable-Laying: From Great Eastern to Monna Lisa

The resilience of submarine electricity cables is often underestimated. While failures can be disruptive, repairing a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) cable is typically faster and less hazardous than fixing an undersea natural gas pipeline. There is no pressurized gas containment or risk of explosion — just technically demanding but well-understood electrical work. This makes HVDC interconnectors a more resilient and safer long-term investment.

A historical comparison is instructive. The Great Eastern’s first attempt to lay the transatlantic telegraph cable in 1865 ended in failure when the cable snapped mid-ocean. The ship returned to the site in 1866 after successfully laying the first transatlantic cable in its second attempt. The crew located and retrieved the lost cable, spliced it, and successfully completed the second connection across the Atlantic — an extraordinary feat of perseverance and technical skill over 150 years ago. When I read this as a child, I found this repair to be very impressive.

In the 19th century, the Great Eastern was the only vessel capable of carrying and laying a transatlantic cable. Today, that pioneering legacy continues with a new generation of specialized cable ships. One prominent example is the Monna Lisa, Prysmian Group’s latest cable-laying vessel.

With a full-load displacement of approximately 35,000 tonnes, the Monna Lisa measures 185 metres in length and 34 metres in width. It features two large-capacity cable carousels (7,000 and 10,000 tonnes), advanced DP3 dynamic positioning systems, and high bollard pull capacity for deep-sea operations. Ships like Monna Lisa are what make a transatlantic project like NATO-L technically and operationally feasible.

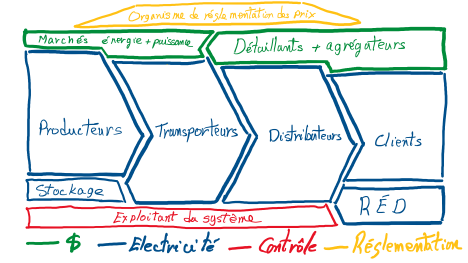

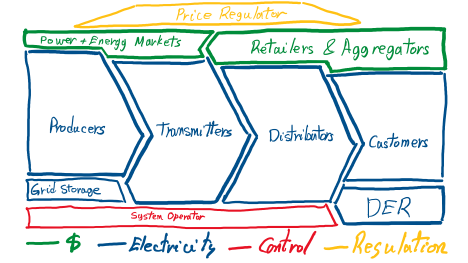

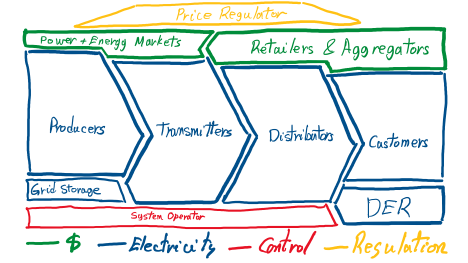

The Market Challenge: Bridging Different Regulatory Worlds

A key issue is that Europe and North America operate under very different market structures:

- Europe has liberalized and competitive wholesale and capacity markets.

- Eastern Canada and parts of the U.S. Northeast operate within monopoly frameworks or hybrid regulated systems.

For NATO-L to work effectively, mechanisms must be created to allow power trading across these systems. Options could include:

- Creation of a merchant export entity operating under EU rules.

- Long-term bilateral PPAs with EU system operators.

- New intergovernmental frameworks under the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) umbrella.

The advocates for this initiative will need to determine a financial structure that allows all involved parties, including buyers and sellers, to profit in line with their respective levels of risk tolerance.

Beyond Economics: Strategic and Geopolitical Dimensions

NATO-L also holds strategic relevance at a time when transatlantic alliances are under pressure. With the U.S. adopting increasingly protectionist policies and stoking annexationist rhetoric, Canada has a vested interest in diversifying its energy partnerships and deepening ties with Europe.

A transatlantic energy corridor would:

- Position Canada as a trusted supplier of clean, reliable power.

- Bolster Europe’s shift away from fossil fuels and dependence on autocratic regimes.

- Enhance NATO’s collective resilience through non-military infrastructure.

- Mitigate climate risks by connecting regions with complementary weather patterns and renewable generation profiles.

This strategic dimension could also unlock institutional or financial support from the European Union. The NATO-L project seems to align with the goals of REPowerEU, the EU’s flagship plan to reduce fossil fuel imports, accelerate renewables, and strengthen cross-border infrastructure. By facilitating transatlantic integration and flexible use of dispatchable hydro, NATO-L contributes directly to those aims. Under REPowerEU, projects that enable decarbonization, energy diversification, and grid resilience are candidates for support through EU coordination or funding instruments.

I estimate that the project could help displace about €1 billion worth of annual natural gas imports and reduce emissions by around 20 million tonnes of CO? per year — primarily by enabling flexible clean dispatch during Europe’s peak demand periods and reducing the curtailment of renewable generation.

By my calculations, the project could also help displace about €1 billion of annual natural gas imports in Europe and cut about 20 million tonnes of CO? per year.

Conclusion: A Second Transatlantic Revolution

The Great Eastern cable of 1866 wasn’t transformative because it was cheap. It was transformative because it reshaped the world’s economic and political interactions.

NATO-L has the potential to do the same for the clean energy era.

By leveraging time zones, dispatchable hydro, and advanced HVDC technology, it can unlock deep decarbonization, transatlantic stability, and real economic returns. But only if market structures evolve to meet the opportunity.

Just as the telegraph enabled global finance, diplomacy, and industry to flourish, NATO-L can become the backbone of a more integrated and resilient net-zero economy.