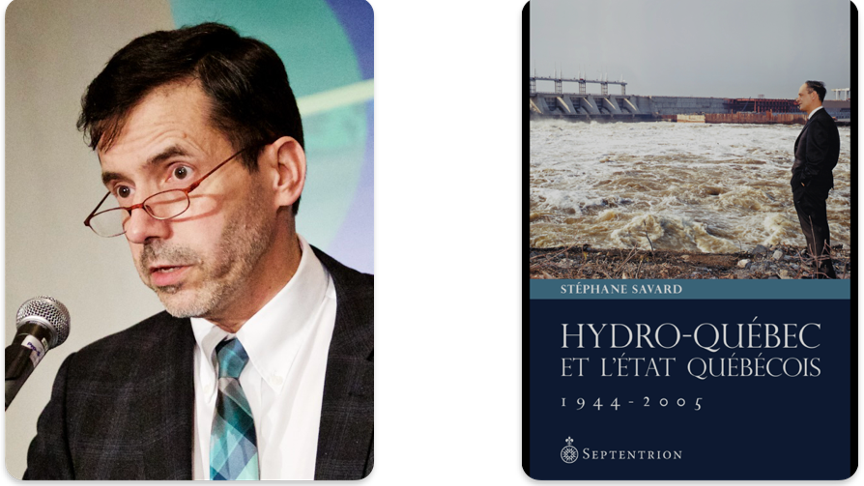

S’il y a un livre que je recommande souvent pour mieux saisir les relations entre l’État québécois et son plus important outil économique, c’est bien Hydro Québec et l’État québécois, 1944-2005 de l’historien Stéphane Savard .

Ce n’est pas un livre d’entreprise ni un pamphlet politique : c’est une œuvre rigoureuse et nuancée qui replace les grandes décisions énergétiques dans leur contexte social, économique et institutionnel. On y suit la montée d’Hydro-Québec comme symbole du Québec moderne, mais aussi les tensions — parfois productives, parfois paralysantes — entre la société d’État et le gouvernement qui la possède.

Savard met en lumière :

- le rôle de la nationalisation dans la Révolution tranquille ;

- les choix d’investissement dans les grands barrages du Nord ;

- l’évolution du modèle de gouvernance et de régulation jusqu’en 2005.

Un livre essentiel, mais aujourd’hui incomplet.

L’ouvrage s’arrête en 2005, et ne couvre donc pas les changements majeurs survenus depuis, comme :

- le virage commercial sous la présidence d’Éric Martel (2015-2020), et son objectif, depuis oublié, de doubler les revenus de l’entreprise ;

- la réduction du rôle de la Régie de l’énergie dans la régulation du secteur ;

- les tensions entre le gouvernement et la présidente Sophie Brochu ;

- le repositionnement stratégique d’Hydro-Québec sous Michael Sabia, dans un contexte de transition énergétique accélérée.

Mais malgré cette limite temporelle, Hydro-Québec et l’État québécois reste une référence incontournable pour toute personne intéressée par l’histoire énergétique du Québec — ou simplement par la façon dont une société façonne ses outils collectifs.

À lire… et à compléter avec une réflexion sur les vingt dernières années.

#HydroQuébec #Histoire #Énergie #PolitiquesPubliques #Québec #TransitionÉnergétique