The deep integration of Canada’s electricity grid with the United States has long provided economic benefits, particularly through efficient cross-border energy trade. Provinces like Québec, Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia have leveraged this interconnected system to export surplus hydroelectric power, stabilize supply and demand, and generate revenue. However, this integration also presents strategic vulnerabilities, especially as geopolitical tensions and U.S. policy shifts introduce new risks to Canadian utilities.

With the rising risks of U.S. economic leverage, regulatory changes, and even annexation rhetoric, Canada must rethink its approach to electricity interconnections and grid governance. Should Canada reduce its reliance on U.S. interconnections? Should it establish independent system operators (ISO) that cross provincial boundaries? Should Canada develop its own electricity interconnections, replacing reliance on the North American Eastern and Western Interconnections?

One province already operates with a degree of electricity sovereignty: Québec. Hydro-Québec runs a largely independent electricity network, relying on its own grid and generating stations, as well as in Labrador, while selectively exporting and importing power to U.S. markets. This model offers Canada an example of how to maintain control over electricity supply while still engaging in cross-border trade on its own terms. The question remains: should Canada as a whole follow suit?

Strategic Vulnerabilities in the U.S.-Canada Electricity Trade

Canada’s electrical infrastructure is not a unified, nationwide network but rather a patchwork of provincial grids, many of which have stronger north-south ties to the U.S. than east-west connections to other Canadian provinces.

The U.S. ties provide stability and allow for profitable electricity trade but also expose Canada to risks such as:

- Geopolitical Leverage: The U.S. could use electricity trade as a bargaining tool in broader economic or security disputes, imposing tariffs, price caps, regulatory barriers, or restrictions on Canadian electricity exports.

- Regulatory Dependence: Canadian utilities must comply with U.S.-based reliability standards set by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) and its regional entities, leaving Canada vulnerable to U.S. policy changes. Incidentally, the original name was the U.S. National Electric Reliability Council, later changed to “North American” in recognition of Canada’s participation.

Security Risks: Cross-border interdependencies create cybersecurity risks. If the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) or related agencies like the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) face budget cuts (as seen by the Federal Aviation Administration, FAA), oversight of grid security could weaken, potentially exposing Canada to reliability threats. Furthermore, recent developments suggest the U.S. is no longer characterizing Russia as a cybersecurity threat, raising concerns about the adequacy of U.S. defensive measures against potential cyberattacks. (The Guardian)

These concerns align with findings from the Standing Committee on Natural Resources’ 2018 report, ****************“Strategic Electricity Interties”, which emphasized the need for greater interprovincial energy transmission. The report highlighted that Canada’s reliance on north-south interconnections limits energy security and economic flexibility, reinforcing the urgency for a stronger national electricity strategy.

How the U.S. and Canadian Grids Connect—and Why It Matters

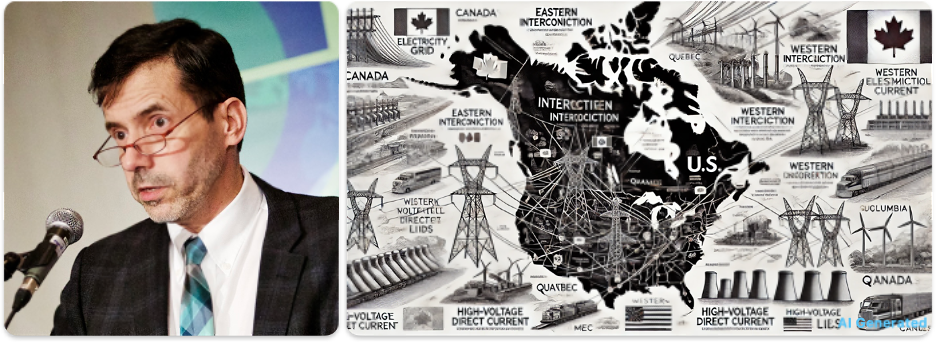

The North American power system consists of multiple interconnected grids, called “interconnections”, that operate in coordination but are not all synchronized. An interconnection refers to a large-area electrical system where multiple power networks operate in synchrony, allowing electricity to flow seamlessly across vast regions. These systems all run at around 60 Hertz (Hz), but not exactly in phase. Each interconnection maintains its own balance of electricity generation and demand, with only limited transfer capacity between them.

The United States and Canada share several major power interconnections that facilitate electricity trade and reliability coordination.

- Eastern Interconnection: Covers most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains, including Ontario, Manitoba, and the Maritimes. It is the largest of the interconnections.

- Western Interconnection: Covers British Columbia and Alberta, extending into the western U.S. states.

- Québec Interconnection: Unlike the rest of Canada, Québec operates as a separate interconnection, using high-voltage direct current (HVDC) and other asynchronous ties to connect to the Eastern interconnection rather than synchronizing with it.

- Texas and Alaska Interconnections: These U.S. systems are also independent and not synchronized with the Eastern or Western Interconnections, though they do not directly impact Canadian utilities.

Who Really Controls Canada’s Grid? The Role of NERC, NPCC, WECC, and MRO

While Canada controls its electricity resources, because of the common interconnections, grid reliability is heavily influenced by NERC and its regional entities, which enforce standards across North America to coordinate cross-border electricity flows and reliability planning, including:

- NPCC (Northeast Power Coordinating Council): Covers Québec, Ontario, the Maritimes, and the U.S. Northeast states.

- WECC (Western Electricity Coordinating Council): Oversees British Columbia and Alberta, ensuring coordination with the U.S. western states.

- MRO (Midwest Reliability Organization): Includes Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and part of Ontario, integrating with the U.S. Midwest.

Since all these organizations operate under NERC’s authority, Canadian utilities must comply with U.S. regulatory standards, even when serving domestic markets. This means that if U.S. national security concerns or trade policies shift, Canada could face regulatory constraints beyond its control.

Canada-Only Interconnections: An Alternative to the North American Grid

Québec operates its own separate interconnection, distinct from the Eastern and Western Interconnections used by the rest of Canada. It is the only province in Canada with an autonomous grid, giving it strategic control over energy flows and trade policies, distinct from the Eastern and Western Interconnections used by the rest of Canada. It is the only province in Canada with a fully autonomous grid, giving it strategic technical control over energy flows and trade policies. The Québec interconnection has HVDC and other asynchronous ties to the U.S. and the rest of Canada, allowing it to regulate cross-border electricity flow independently.

This separation was originally designed to protect the Eastern Interconnection from disruptions caused by Québec’s long-distance transmission lines carrying hydroelectric power from the north. The independent structure allows Québec to efficiently manage its unique energy system, which is almost entirely hydro-based, while also maintaining full control over its grid operations and trade policies. Notably, because of this independent interconnection, Québec was unaffected by the massive 2003 Northeast Blackout that began in Ohio, while Ontario suffered extensive outages. This blackout disrupted power for over 50 million people, demonstrating how reliant the rest of Canada is on U.S. grid stability. This incident highlights the vulnerability of Canadian grids to disruptions originating in the U.S.

This model gives Québec greater independence, insulating it from potential U.S. regulatory or reliability challenges. This model sets a precedent for the creation of Canada-only interconnections, reducing exposures to the U.S. portions of the Eastern and Western Interconnections. Given Canada’s vast geography, this would likely require two or more independent interconnections linked by new high-voltage direct current (HVDC) interties.

The transition to Canada-only interconnections would be a long-term, complex endeavour, likely requiring at least a decade to fully implement. A relevant example is the Baltic states’ recent separation from the Russian grid and synchronization with the European Union’s network. This transition required extensive investments in grid modernization, infrastructure upgrades, and international coordination, taking over 15 years from planning to execution. The Canadian grid would require similar long-term planning to ensure a smooth transition away from reliance on the U.S. interconnections. This underscores the significant investment, coordination, and infrastructure development necessary for such a shift.

Conclusion: The Need for a Canadian Electricity Strategy

A Canada-only interconnection system, supported by HVDC east-west transmission, would allow Canada to balance renewable energy, ensure reliability, and reduce dependence on U.S. policies and regulations. Québec already serves as a model for greater energy independence, proving that Canada can maintain sovereignty while selectively engaging in energy trade.

While this path presents challenges—including infrastructure costs and provincial resistance—it may be the best long-term strategy for protecting Canada’s energy sovereignty and grid resilience.