Throughout my career, first as an engineer and later as a strategy consultant, I have worked with organizations facing major transitions. The liberalization of telecommunications, the shift from analogue to digital, and the emergence of the internet and mobile technologies fundamentally redefined business models that had once seemed stable.

Today, the energy sector is undergoing a transformation of a comparable magnitude.

(LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/planning-during-energy-transition-benoit-marcoux-thshe/)

Traditional strategic planning rests on an implicit assumption: predictability. Past trends serve as a guide. Models converge toward a central scenario. Sensitivity analyses test variations around known variables.

This logic works reasonably well in environments that evolve slowly.

During an industrial transition, it becomes misleading.

The energy transition combines rapid technological evolution, deep regulatory change, persistent geopolitical instability, the physical impacts of climate change, and potential disruptions capable of reshaping value chains. Investment decisions are capital-intensive, time horizons are long, and mistakes can be costly.

In this context, the strategic question is no longer “What is the most probable scenario?” but rather, “How do we execute a plan capable of absorbing major bifurcations without losing coherence?”

Here is the overall logic I propose.

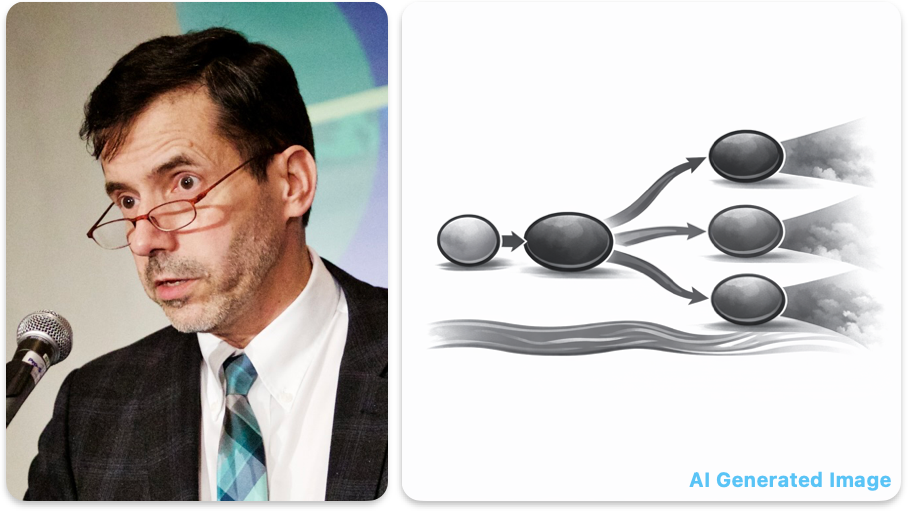

The diagram condenses the approach: an initial diagnosis, possible events, plausible bifurcations, cones of uncertainty, and actions that influence probability and impact. It helps visualize the shift from a static snapshot to a set of possible trajectories, each surrounded by a zone of uncertainty and shaped by concrete decisions.

1. Start with a structured diagnosis

For simplicity, let us use the SWOT analysis framework (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats).

Strengths are current internal elements that provide a recognized comparative advantage.

Weaknesses are internal elements that limit performance but can be corrected.

Opportunities are realistic avenues for progress built on an existing functional base. They can be developed or captured.

Threats are external or systemic developments that may cause harm. They cannot be directly controlled, but the response can be managed.

The SWOT analysis provides a structured snapshot. It distinguishes the internal from the external, what works well from what does not. But it remains static. It does not yet identify what is decisive.

In energy, this diagnosis may concern positioning within value chains, dependence on critical inputs, security of fuel supply where relevant, the robustness of generation and distribution infrastructure, technological adaptability, or financial resilience.

In periods of transition, one variable becomes central: adaptive capacity. Strength can turn into rigidity if it locks the organization into an outdated model. A weakness can be corrected if identified early and addressed with discipline.

2. Project forward: what could happen?

The next step is to translate opportunities and threats into concrete events that could materialize.

We move from snapshot to anticipation.

Each event is assessed along two simple dimensions:

- Its probability.

- Its impact.

This logic applies symmetrically to adverse and favourable developments.

A threat becomes an evaluated risk. An opportunity becomes a strategic possibility analyzed with equal rigour.

The objective is not to produce an elegant matrix. It is to identify the events capable of genuinely altering the trajectory.

An event with a low probability but high impact may be structurally significant. Conversely, a frequent event with limited impact belongs to routine management.

This is where dominant variables emerge.

3. From dominant variables to strategic bifurcations

High-impact events define plausible branching points.

Scenarios are not invented to explore imagination. They correspond to bifurcations linked to structurally significant variables.

One can distinguish a central scenario and a limited number of alternative scenarios associated with the materialization of a major risk or a significant breakthrough.

Planning becomes an exercise in clarifying bifurcations, not multiplying scenarios.

4. Acting on probability and impact

Once dominant variables are identified, the strategy becomes operational.

For each risk and each opportunity, two categories of action can be distinguished.

First category: act on probability. For a risk, this may involve diversifying markets, reducing critical dependencies, or strengthening alliances. For an opportunity, it may involve investing in research and development, launching pilot projects, or forming industrial partnerships.

Second category: act on impact. For a risk, this may require increasing operational flexibility, redundancy, or absorption capacity. For an opportunity, it may mean amplifying positive effects, for example, by reserving industrial capacity or securing market access.

The strategy thus materializes as a portfolio of concrete options.

An option is an activity undertaken today to influence the probability or impact of an event tomorrow, while preserving the freedom to decide later whether to fully commit. It may involve preparatory investments, partnerships, capability building, regulatory positioning, or pilot projects.

Crucially, an option does not oblige execution. It creates the right, not the obligation, to act. Some options will expire unused. Some preparatory efforts may appear wasted in hindsight. That is not a failure of strategy; it is the price of flexibility in a period of structural uncertainty.

5. Testing robustness: the cone of possibilities

Within a given scenario, sensitivity analysis tests the robustness of decisions.

Key assumptions are varied around a defined trajectory: capital expenditure, cost of capital, energy prices, timelines.

These variations define a cone of possibilities.

A robust decision is one that remains coherent within that cone.

It must be recognized, however, that classical sensitivities operate on known variables. They do not always capture structural disruptions. This is why identifying dominant variables and plausible bifurcations upstream is critical.

One essential point deserves emphasis: this approach remains relevant even if we do not anticipate exactly which events ultimately materialize. Actions undertaken to influence probability or impact are often reusable across different situations. Diversifying markets, developing capabilities, strengthening operational flexibility, or building strategic partnerships increases resilience to a wide range of shocks. The objective is therefore not to predict the future precisely, but to prepare for the unpredictable.

6. An evolving process

Strategic planning in a period of transition is not a one-time exercise.

By repeating the analysis regularly, some bifurcations may disappear while others emerge. Cones of possibilities may narrow or widen. The hierarchy of dominant variables may shift.

We cannot predict the future in every detail, especially in an industrial transition such as the one currently reshaping the energy sector.

But we can structure uncertainty.

Experience from previous transitions has taught me this: organizations that navigate such periods successfully are not those with the best scenario. They are those that have organized their ability to pivot.

That is when planning stops being a modelling exercise and becomes an instrument of execution.

If you look at your current strategic plan, does it truly organize your ability to pivot, or does it still assume continuity?