The Government of Québec has tabled Bill 34[1]that simplify the rate-setting process for Hydro-Québec Distribution.[2]Essentially, most distribution rates are frozen for 2020, and then adjusted for inflation until 2025, when a rate review would occur. Additionally, the bill requires Hydro-Québec to reimburse to customers of some $500 million before 1 April 2020.[3]It should be noted that Hydro-Québec currently has the lowest residential rates in North America.[4]

This Bill is a significant change from the traditional rate base rate-of-return regulation that previously subjected Hydro-Québec to yearly rate filing. Based on my personal marketing experience in the electricity industry, this post outlines my views of how Bill 34 may change some of Hydro-Québec business drivers when dealing with its vendors, presumably leading Hydro-Québec to faster decision-making in purchasing, smarter assessment of costs, and a greater appetite for innovative solutions.

Before: Traditional Rate Base Rate-of-Return Regulation

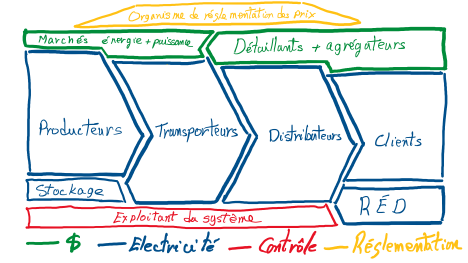

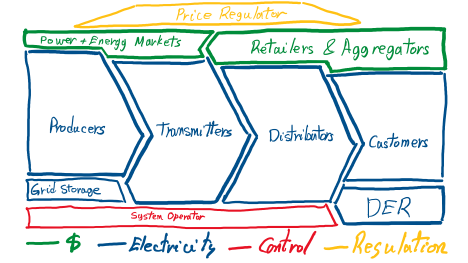

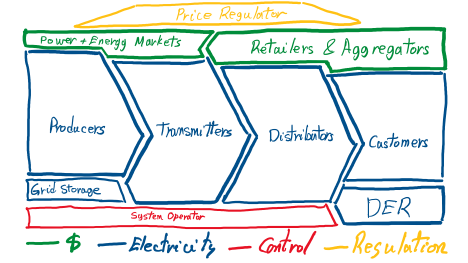

The electricity distribution business is a natural monopoly. This means that it is in the interest of society to have just one distribution utility in a given territory. It is easy to understand the rationale: you would not want to have multiple sets of poles along roads; one set is more than enough. However, left to itself, a distribution utility with a monopoly could charge unreasonable rates for use of its bottleneck facility.[5]

In most of Canada and the United States, electric utilities are regulated using a traditional rate base rate-of-return regulation regime. Under this regime, the sum of all regulated costs – essentially operating expenses, depreciation on assets (resulting from past capital expenditures), interests on debt, taxes, as well as an allowed shareholder returns on investments (i.e. a reasonable profit) – are recovered from customers. This is called revenue requirement or required revenues. Required revenues are allocated across the customer base in a variety of ways, primarily on the basis of the energy distributed (cents per kilowatt-hour, ¢/kWh), as well as peak load (dollars per kilowatt, $/kW) for some commercial and industrial customers. In practice, different classes of customers get different rates, but revenues projected during a regulatory rate case have to be equal to revenue requirements. If there is a significant variance between the projected revenues and the actual revenues in a year, adjustments are normally made in subsequent years.[6]

Obviously, regulated utilities are not allowed to spend anyway they want: they have to prove to their provincial regulator – the Régie de l’énergie in Québec, the Alberta Energy Board, the Ontario Energy Board, etc. – that their costs (both operating expenses and capital expenditures) are necessary and prudent. These arguments are aired during public rate cases – yearly in the case of Hydro-Québec, up to now – during which various interveners, typically representing customer groups, submits reports and ask questions. The process can be slow, adversarial and excruciating as all details of operations are looked at and need to be justified – the regulator often does not trust the utility and even activities and investments that a utility may present as essential may not be approved.

Rate-of-return regulation of utility monopolies has served relatively well as a market substitute for a century, but it has its drawbacks. I’ll retain three issues for discussion here: slow innovation, poor service quality, and uneconomic decisions.

Innovation tends to be among the casualties of rate-of-return regulations: the slow regulatory cycle, the public scrutiny and the second-guessing by interveners makes utilities extremely risk-averse and slow to integrate new technologies. For example, as part of rate cases, utilities sometimes specify models of power equipment, which become the standard products used in the network. Because another complex homologation process would get in the way, product selection may not be revised for many years, even decades, often until the vendor cease production. However, over time, utilities often end up customizing those products, based on experience or new needs, rather than seeking newer products.

Rate-of-return regulation is an economic form of regulation that does not properly account for service quality. It is difficult to integrate service quality metrics in this regulatory framework and offering varying levels of service quality depending on willingness to pay is not practical. Not surprisingly, electric utilities tend to have negative Net Promoter Scores (NPS), a loyalty measure, with generally far more detractors than promoters among customers.[7]

Since their revenues are practically known in advance following rate setting, regulated utilities look at their business upside-down in comparison to companies operating in a competitive, free market:

- Shareholders earn a return on all utility assets – the more, the better. New investments mean a larger asset base, on which the shareholders are allowed to claim a return, meaning that net income will also be higher. There is a strong incentive for utilities to buy more equipment or to gold-plate it, although interveners may oppose, and regulators may not agree.

- Regulated utilities effectively pass operating expenses to their customers. Indeed, lowering (or increasing) operating expenses simply lowers (or increases) required revenues, but net income remains unaffected. Yet, the regulatory process tends to compress controllable operating expenses (like customer service or maintenance) in expectation of raising efficiency by the utility. Utilities may actually go along, shareholders preferring to compress operating expenses than investments in assets.

For vendors, traditional rate base rate-of-return regulations mean that making normal sales arguments often does not make sense in a utility world:

| What vendors may say | What utility people may think |

| “You would be the first in the industry to implement this new technology.” | “…And go through hell trying to get it approved.” |

| “You’ll save on capital expenditures with this new equipment.” | “Why would we do this? Shareholders want to justify more capital expenditures, not less.” |

| “You’ll be making more profit by adopting my cost-saving solution.” | “No, we’ll have to pass on the savings to customers at the next rate case and not make more profit.” |

Surprisingly, it seems that few vendors understand this traditional utility buying logic, although it is very much the normal case across Canada and the United States. However, Bill 34 is changing all this in Québec.

What Is Bill 34 Changing?

Bill 34 freezes most distribution rates for 2020, followed by yearly adjustments for inflation until 2025, when a rate review would occur. Therefore, Hydro-Québec would no longer have to file rate applications, with detailed costs justifications, every year. Under the Bill, Hydro-Québec is not required to obtain authorization for its infrastructure investment projects and changes to the electricity distribution network. Similarly, commercial programs do not need approval. In contrast to traditional regulation, Bill 34 effectively disconnects costs and revenues for 5 years and should introduce more common business decision-making.

Bill 34 also stops the Régie efforts to move to a Performance-Based Regulation (PBR). PBR is increasingly popular to regulate utilities[8]. In Canada, Alberta has adopted PBR.[9]Another good example is Great Britain, with its RIIO (Revenue = Incentives + Innovation + Outputs) framework.[10]PBR generally aims to balance multiple variables, such as quality of service and costs, while freeing utilities to innovate. Without presuming of the rationale behind Bill 34, it may be that the very low costs of electricity in Québec in comparison to the jurisdictions where PBR was implemented, as well as Hydro-Québec’s renewable generation fleet, present a simpler approach toward the same objectives.

After: Faster, Risk-Taking and Innovative?

Hydro-Québec remains a natural monopoly, without direct competitive pressure. However, with Bill 34, decision-making should become much closer to that of “ordinary” commercial business, with a new-found flexibility and a greater drive toward efficiency and business innovations. Hydro-Québec will be incentivized to reduce costs to increase net income, as revenues will be stable (after inflation). In particular, the new framework removes the bias toward capital expenditures and rewards a smarter control of operating expenses. For instance, with greater flexibility, Hydro-Québec might increase maintenance and extend life of some power equipment at the same time that it might replace other assets with advanced systems – all in the name of efficiency.

All this may change how Hydro-Québec will interact with equipment and service vendors, although any change to purchasing decision-making will undoubtedly depend on management decisions and may be slowed by the natural inertia of the company.

Nevertheless, Hydro-Québec may become more open to acquire new products and services from new vendors, with a corresponding risk for established vendors. High-end or customized (and therefore more expensive) products from established vendors may be especially at risk of substitution by less expensive or industry-standard ones. In some cases, the number of vendors supplying a type of product dwindled to just one over the years; it now may be that Hydro-Québec will seek to split contracts with a competitor to try to bring down costs on commodity products. On the other end, like common in other industries, Hydro-Québec may also seek broad strategic partnerships for more complex products, with favorable contract terms for Hydro-Québec in exchange for a vendor exclusivity in some product categories.

With the greater flexibility brought by Bill 34, Hydro-Québec may also become more inclined to try out innovative products or systems in its distribution network, and we could see faster decisions to deploy those innovations. This might come at an opportune time, as other utilities introduced new grid technologies in order to support distributed generation (especially solar) at a very large scale[11]; Hydro-Québec could learn from the vendors involved in these deployments.

Similarly, Bill 34 might enable Hydro-Québec to accelerate the launch of new products or services to its customers, possibly in collaboration with external vendors. Hydro-Québec has been innovative in researching new uses for electricity and energy efficiency system, going as far as building houses to test smart home technologies.[12]Hydro-Québec publicly expressed interest in how smart home, solar generation, energy storage and microgrids could impact its network.[13]Other utilities have already introduced services and products to their customers around these concepts, like BC Hydro (CaSA smart thermostats)[14], Green Mountain Power (Tesla batteries and FLO smart electric vehicle chargers)[15], Hydro Ottawa (Google smart assistant),[16]and many more; it would not be surprising to see Hydro-Québec following suit.

What May Not Change

While Bill 34 will change many things, some important practices should remain. For example, Hydro-Québec is extremely serious about cybersecurity[17]; vendors should still expect to have to meet stringent cybersecurity requirements, for good reasons. As a Québec crown corporation, Hydro-Québec also remains subjected to normal government buying policies, like requiring bids beyond certain amounts and strict rules when dealing with vendors[18]– this too will remain.

Contrary to performance-based regulatory regimes like RIIO in Great Britain (see above), Bill 34 does not provide explicit incentives to improve the reliability of the electricity service. While this is not a change from the current regulatory regime, it should be noted that the reliability of Hydro-Québec electricity services has been degrading over the last years.[19]However, repairing the network after an outage does cost money, and some vendors could highlight how their solution prevent outages or reduce the cost of repairs. Furthermore, Hydro-Québec management could conclude that maintaining sufficient reliability is essential to avoid a decision to return to traditional regulation in 2025.

Also, Bill 34 specifically maintains Hydro-Québec’s obligation to file an annual report. Those reports include a wealth of information on the organization, the performance and the financial situation of Hydro-Québec.[20]

Finally, utilities, including Hydro-Québec, publish public performance indicators.[21]Usually, those indicators are also used in management incentive plans. Showing the impact of a solution on performance indicators will remain a sound sales tactics when selling to utilities.

Closing Words

Once Québec’s national assembly adopts Bill 34, probably in the Fall, it will certainly become an experiment that will be carefully watched by Canadian regulators. Leveraging the low costs of renewable electricity in Québec, it may encourage greater efficiency and business performance by Hydro-Québec, without the complexity of a performance-based regulatory regimes.

For vendors, the Bill may also fundamentally change how Hydro-Québec should be approached, with potentially a much greater attention to total costs and partnerships than before.

Do not hesitate to contact me to discuss further.

Benoit Marcoux, benoit@marcoux.ca, +1 514-953-7469.

[1] See “An Act to simplify the process for establishing electricity distribution rates”, http://www.assnat.qc.ca/en/travaux-parlementaires/assemblee-nationale/42-1/journal-debats/20190612so/projet-loi-presentes.html, accessed 20190614.

[2] Bill 34 only affects the distribution division of Hydro-Québec. The transmission (TransÉnergie) and generation (Production) divisions are not affected.

[3] See http://news.hydroquebec.com/en/press-releases/1510/electricity-rates-adoption-of-a-simplified-approach-that-will-guarantee-low-rates/, accessed 20190620.

[4] See http://www.hydroquebec.com/residential/customer-space/rates/comparison-electricity-prices.html, accessed 20190615.

[5] Note that the natural monopoly does not extend to energy retail and generation. In many jurisdictions, notably in most of Alberta, Texas and Europe, there are many energy retailers buying electricity from generators and offering various plans to customers. However, this energy is supplied through electricity distributors that have the poles and conductors up to customers’ homes. In Canada, provinces other than Alberta and Ontario have only vertically integrated distributors and retailers, i.e., the distributor is also the only retailer of electricity.

[6] To some extent, Bill 34 is the result of lack of adjustments from over-earning in previous years, as the provincial government, owners of Hydro-Québec, kept these surpluses. This resulted in a delicate political situation, as many people saw this as a disguised tax.

[7] See CEA Opinion Research, 2014 National Public Attitudes for NPS of Canadian utilities, and https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Net_Promoter, accessed 20190615, for an overview of the concept.

[8] See http://go.woodmac.com/webmail/131501/471713673/8ec22b38df7f81ef4f8278af14095e1bb711214dffd0ee90dc9a250ab8bb5970, accessed 20290619, for an overview of PBR adoption in the United States.

[9] See http://www.auc.ab.ca/pages/distribution-rates.aspx, accessed 20190615.

[10] See https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/network-regulation-riio-model, accessed 20190615.

[11] For example, there are 840,878 residential solar projects in California (https://www.californiadgstats.ca.gov/charts/, accessed 20190617) but only about 700 in Québec (see https://www.lapresse.ca/affaires/economie/energie-et-ressources/201903/22/01-5219334-mini-boom-de-production-denergie-solaire-au-quebec.php, in French, accessed 20190617). Integrating a large number of distributed generators in a distribution network is challenging, and utilities in some other jurisdictions had to innovate to make it work.

[12] See https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1016006/hydro-quebec-maisons-futur-shawinigan-energie-solaire-thermostats(in French), accessed 20190617.

[13] See http://plus.lapresse.ca/screens/f2ad982b-9fda-469f-a3f2-86116ab0a46a__7C___0.html(in French), accessed 20190617.

[14] See https://www.bchydro.com/powersmart/energy-management-trials/casa-thermostat-trial.html, accessed 20190617.

[15] See https://greenmountainpower.com/products-all/, accessed 20190617.

[16] See https://hydroottawa.com/save-energy/innovation/smart-audio, accessed 20190617.

[17] For example, Hydro-Québec is funding an industrial research chair in smart grid security at Concordia University – see http://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/Chairholders-TitulairesDeChaire/Chairholder-Titulaire_eng.asp?pid=981, accessed 20190617.

[18] See https://www.hydroquebec.com/suppliers/becoming-supplier/safe-ethical-and-responsible-procurement.html, accessed 20190618.

[19] The average number of minutes of outages per Hydro-Québec customer, excluding major events like storms, has been steadily increasing, from 126 minutes in 2013 to 181 in 2018. See http://www.regie-energie.qc.ca/audiences/RappHQD2013/HQD-09-02-Indicateursdeperformance.pdfand http://publicsde.regie-energie.qc.ca/projets/501/DocPrj/R-9001-2018-B-0060-RapAnnuel-Piece-2019_04_18.pdf, respectively for 2013 and 2018, in French, accessed 20190617.

[20] See http://www.regie-energie.qc.ca/audiences/RapportsAnnuels_DistribTransp.html, accessed 20190615, for past annual reports in French.

[21] See http://publicsde.regie-energie.qc.ca/projets/501/DocPrj/R-9001-2018-B-0060-RapAnnuel-Piece-2019_04_18.pdffor Hydro-Québec’s 2018 performance indicators, in French, accessed 20190618.